|

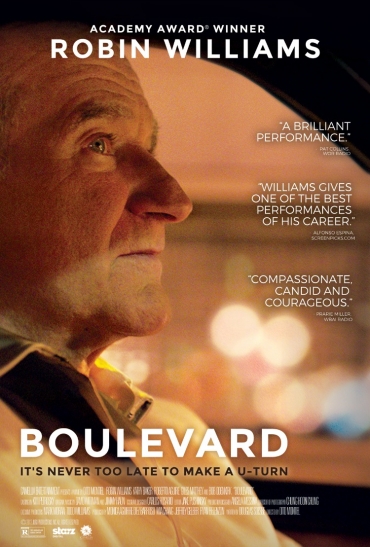

Our new "How I Broke In" article has been published by Final Draft. We spoke with Douglas Soesbe, writer of "Boulevard". (Robin Williams last film). He is also a story analyst with Universal and has some great insight into the studio thought process. You can read the interview here.

1 Comment

We are pleased to announce that we will be writing a regular column for Final Draft called, "How I Broke In". We will be interviewing Hollywood screenwriters to talk about the industry, what they're working on and how they came to break in to the industry in the first place.

In this column, we speak with Ben Ripley, writer of Source Code and Boychoir. We hope you enjoy. Ben Ripley - How I Broke In by Dustin

Collaborative scriptwriting is one of the most intense creative endeavors I've ever been a part of and I'm lucky enough to do it with one of my favorite people. I've known my partner since college and we were friends long before we worked together, so when I tell Dave to shut up and he tells me I've got a bad idea it's like water off a duck's back. I know he respects my ideas and he knows I think he's got a boat load of talent. Getting the best project is our goal and we are pretty ruthless about getting that. Lately we've been getting some attention to our process and I thought I might jot down my thoughts about that. Being a writer is nice and safe. I can sit in my house and type all day with only minor interaction with my wife (a blog topic I'm not quite ready to tackle). Maybe, IF I get the the piece to a place where I'm happy with it, I'll show it to an editor or a friend and get some feedback. Collaboration is rarely the name of the game and only if I'm writing poetry or a song for someone else will it become necessary to "share" the work. This process was entirely new to me when I started working on my graphic novel. I came to film from animation, where nothing you do is your own, a place of re-making and do-overs. For instance: The first thing we practiced at animation school was how to copy things perfectly, so that the line weight of our pencil was the same as whoever was drawing the master drawings. In traditional animation you have people doing master drawings and working out the timing sheet, lead animators making key frames, assistants drawing in-betweens, inkers tracing the final drawings onto acetate, and painters who paint the back side of each frame without going over the inked edges of the acetate drawing. Then you send it all to a camera man who shoots the frames (following the timing sheet, you hope) and in the end you have a cartoon. This process requires a lot of skill at every position, and more importantly, communication between everyone involved. I found that to be the same on film sets, advertising agencies, and large corporate art departments throughout my career as a professional artist. This main thing this background taught me was how to work with other creative people. Most importantly, how to keep my own feelings about the work under control, and how to speak about changes in others contributions to the work. The key is to do this without making collaborators feel bad. Most creatives, especially ones who haven't' spent a lot of time in a sharing environment, are very attached to the work on a personal level. Remember: When giving and taking criticism about the work, what creatives hear is about themselves. The key to talking openly about making a better product is a well documented process and there are hundreds of people making books about that and I wouldn't want them to go hungry, so buy their books if you want to. You'll probably learn something. I have found this short, FIVE step process really helpful when dealing with other artists: ONE: Thank you. Your partner just spent a piece of their lifetime on this piece of work. Thank them. This is THE most important piece of advice I have ever been given and will ever give. Compliment them at the start of the process. Sometimes you'll forget, and jump straight to the criticism. See where that gets you and contrast against the compliment first method. TWO: Compliment what works in the piece. You're not partnered with idiots, regardless of how you feel in the moment. This partnership was entered into purposefully and they made a genuine contribution to the work. What's working, even if it's off topic? Nicely done! THREE: Re-visit the theme and purpose of the project. Sometimes we artists get obsessed with a bit of the detail, and not the fairway of intention. When we look back at the main topic, we find ourselves lost in the weeds of detail, and have to work to get back to the green. It is often our contemporaries and partners who ask us to re-evaluate the purpose of our work, and question our sports analogies. Be that guy for your team. Ask the questions that get you back on topic. FOUR: Question the work against the purpose and theme. This is the time to voice your criticism. Don't hold back, but keep your criticisms pointed back on topic. Always use the first person: "I don't like this or this" and try to keep away from generic "that sucks" or "it's no good" type statements. "I don't like it, it sucks." is perfectly reasonable, but be prepared to back up your assessment with reasons. *note* "I just don't like it." is a totally valid reason. FIVE: Come up with a better solution together. If the work is on topic and you just don't like the color, what color would you like it to be? How can a conversation between two characters be streamlined with less dialogue and more action? Staying on topic and focusing on the goal of the project will help move the conversation past hurt feelings. If your partner has run off into the weeds, help them get back into the green by asking leading questions that get their thoughts back on topic. Be sure to keep those notes from the weeds. You never know when that bit of detail is going to be handy later on! Scriptwriting as a group activity can be a real pain in the ass and at worst can lead to alienating friends and collaborators you've spent years trying to pull together. When fear of failure and self doubt begin to creep in you may even alienate yourself. Take the time to remind everyone that we're having fun doing the thing we love, and we're not trying to hurt anyone's feelings. It sounds cheesy, but it will keep your team together. If only long enough to get the work out the door. Remember the film you think you are making is not the film you are making. A movie gets created Three times. Once on the page. Again during production. Finally in post. Because of the collaboration involved the film we write is rarely what we see on the screen. If we are lucky and diligent, it is better. by Dave You don't have to write only about what you know, but you do need to know about what it is you write. A common refrain we have all heard over and over again. We aren't expected to know everything in the world but we have to be open to learning about it. How do we do that? We talk to and hire people who know about the areas we seek to learn. It's a great plan, but it's also fraught with danger. Let me use this example as a way of explanation. When I worked Seized Property for Customs and Border Protection (CBP) we had several items that couldn't be stored in our permanent vault. Whether it be cars, houses, special seizures (such as hundreds of thousands of dollars of vintage wine that needed to in cold storage), or the just plain absurd, like the grizzly bear (supposedly circus trained) that was in the back of a trailer to act a deterrent from the officers finding the thousands of pounds of drugs hidden in there. To fill this void, CBP hired a national contractor to take care of all these special seizures. In turn, the contractor would hire retired CBP employees to oversee the program and make sure everything was correct. The liaison we worked with was a retired Special Agent. He had thirty years in the Agency, twenty of them as a member of management and several extended assignments to Washington DC. The man was connected, he knew it all. Yet, he didn't actually know anything. The national contractor had fallen for the same trap that many filmmakers make when hiring a movie consultant.

So what can this teach us? Make sure you are hiring a person with specific experience in the realm of your story. If you have a story about the backroom politics at a national level, then go after a Headquarters person. If your story is about a local officer, find someone with about five to ten years in who never transitioned away from the field. Have a SWAT story? Make sure you hire someone who actually worked on a SWAT team. Have a completely raw, gritty story that may not put people in the best light? Better not hire the guy provided by the agency whose job it is to make them look good. Don't be blinded by resumes. *Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. Directed by Irvin Kershner. Studio, Lucasfilm (now owned by Disney) by Dave

I've had plenty of people ask me what I think of movies and TV shows centered around law enforcement. Do I like them? Do they piss me off? Do they make me laugh even though they aren't supposed to be comedies? The answer? Yes, to all of them. I love a good police procedural. I love a good film centered around a police officer. I also get mad, or laugh, at shows that really don't know what they're talking about when it comes to law enforcement work. I can tell in about five seconds if the writers or directors have actual experience or are putting forth what they have seen in other movies (correct or not). So, being the humble (wife just snickered) and helpful person I am, let me help sort some fact from fiction in order to make your fictional story more factual. Here are five myths (misconceptions really) I see time and time again.

As an added bonus, I can also say that traveling with your weapon, without armed authorization, also sucks. On another trip back from New York, our Port Director did not give us authorization (she didn't like guns, go figure). I had to declare my weapon in my suitcase to the ticketing representative. First thing she said? Why aren't you wearing it? Then, "I have to see it". So I got my travel case out of my suitcase, opened it and showed her. She said, "All right, but my manager has to see it to clear it." So over came the manager. He said two things, "Why aren't you wearing it?" and, "I have to see it". So out it came again. His response, "All right, but the Port Police have to be the ones to clear it." So I waited for them to respond. Any guesses what they said? "Why aren't you wearing it?" and "I have to see it." Out it comes again. "All right, but TSA has to clear it". Mind you, I have been thirty feet from TSA the whole time. Why I couldn't have gone there first, no one knows. So I go to TSA, "Why aren't you wearing it?" and, "I have to see it." (insert primordial scream here). TSA then proceeded to take out their bomb swiping materials to test my weapon for explosive residue. Really? You think that the tool whose soul purpose in life is to fire projectiles through the explosive force of gunpowder might have residue on it? Turns out, according to TSA, it doesn't. Be afraid. by Dave After spending nearly a decade in Law Enforcement, I can tell you one thing with certainty. I hated my ballistic vest, AKA "The Bullet Proof Vest". They're heavy, they're bulky and almost impossible to wear comfortably. They are also one of the most misunderstood pieces of equipment that law enforcement officers wear.

Bonus: If your character cannot figure out what to do when the suspect is wearing a vest, don't have them shoot the bag of pipe bombs next the suspect so he can die in the explosion. I wish I was making that scene up, but I saw it on TV (so it must be true). First, the bombs won't explode when shot. Second, aiming for the head seems a heck of a lot better of an idea than exploding half the building and innocent bystanders.

*Dumb and Dumber: Written and directed by the Farrelly brothers and produced by New Line Cinema. by Dave

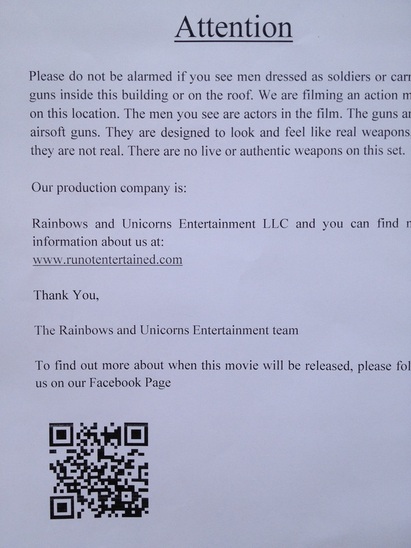

As we begin pre-production on our next film, I am nagged with one small, but constant fear. I really, really don't want our production to be delayed by a SWAT team raid. I know, probably not the most realistic fear, but I'm also the guy who doesn't like being the first one in the water, even in fresh water lakes. It's also not that far-fetched when you think about how many concerned citizens would totally ignore the film equipment and camera crew when they tunnel vision on the men in tactical gear carrying big guns and call the police. So, as a public service, I am going to share some of the steps we are taking to make sure we are not standing against a brick wall, hands behind our head, waiting for the police to sort everything out.

In the end, an ounce of preparation really does go a long way when it comes to safely shooting any scenes with weapons. Please do not take it lightly just because you are shooting with "toy guns". by Cody

Let's talk about the Katana. The katana is one of the most visually recognizable symbols of Japan. A weapon that is renowned for its beauty and killing power. Is it any wonder that it has become the go-to sword of choice in movies? But is it really a “Jack-of-all-trades” weapon that can be used in all situations? The Katana is a superb weapon for the kind of combat it was designed for, killing or maiming an enemy in one hit. It is a weapon designed to end fights quickly and decisively. The reputation and legend of the Katana has, in many ways, placed it on a pedestal in the minds of the general public. But the Katana has many weaknesses that are rarely discussed.

So how does this affect the movie you’re making? Let’s say it’s a zombie movie (one of the most common places to see a Katana). You are dealing with creatures that can only be killed with a thrust to the head or complete decapitation. The Katana is a sword that is made for slashing through the torso, the blade chips on bone and isn't made for thrusting. Is the Katana really the best choice? Sure, one or two zombies and you’re fine. But what about when you are facing a horde and your sword gets progressively worse with each swing? Or would you be better off looking at a European sword? Their design is much better suited for thrusting and cutting through bone. The Katana has its place, but far too often it is a crutch used to make a character appear more exotic or communicate to the audience that “This is the real bad ass of the story”. Some of you may be saying, "It's just a sword". True, but this is the type of things nerds notice. Would it really change your prop outlay or story to have the character using a European sword? No, but you would be light-years closer to gaining nerd acceptance and nerds spend a lot of money on properties they deem acceptable. by Thomas

An often overlooked concept when making military movies, or when using a character with military experience, is building a proper base. What I mean by building a base is constructing an appropriate background for the character so that his skill set and actions make sense. Everyone has heard of Special Operations and often it becomes a catch phrase to explain why a character can single handedly defeat 12 bad guys with nothing more than a paperclip and a killer smile. Hands down the best PR, with regards to Special Operations, goes to the Navy SEALS. Take for example the Bin Laden raid; does anyone really believe that only SEALS participated in that operation? This PR, combined with a lack of military knowledge, has led to stories where we simply need to say that the protagonist was a SEAL and all further actions are taken as acceptable. I would challenge writers and directors to dig a little deeper. The right tool for the job Just as it is important to have the proper tool in construction it is also important to grab the right tool from the Special Operations tool box.

Now let’s say that we have a story that involves a protagonist who has to do something fantastic, such as disarming a bomb on a dam that was planted by a deranged terrorist. Which group should we base our protagonist’s story around a water operation? Navy SEAL. A brute force assault? Rangers. Something so mind bafflingly crazy it can’t succeed? Delta. Understanding the mindset and training of each group Having only experienced the path to becoming a Ranger I will stick to what I know rather than speculate. First you start at basic training; most people understand that this is a grueling course set up to condition you mentally and physically for the tasks of a Soldier. Next comes MOS (Military Occupational Specialty). This school will vary in length and difficulty depending on your MOS (infantry, radio operator, etc...) After this course you are shipped off to Airborne school where you learn to become a paratrooper. Now the fun starts, RASP, formerly known as RIP (Ranger Indoctrination Program). This is a one month course to see if you have what it takes mentally and physically to be a part of Ranger Battalion. There are road marches, runs, land navigation and constant physical exercises and demands that will weed out the field. Once this is completed you have the privilege to become a private at a Ranger Battalion where you will be punished mentally and physically in training and combat until you earn the right to go to Ranger School. Ranger School is a 62 day (Plus 30 if you are from a Ranger Battalion, irony I know) attrition school where you learn about operations orders, combat operations, and leadership in high intensity stressful situations. After all this is done you will be eligible to compete for a leadership position inside Ranger Battalion. Why is all this important? Because each man who got to this point volunteered for it and wanted it. This is an important concept because often movies depict that a particularly dangerous mission is one that soldiers don’t want. Not only do Rangers want this mission they will fight to get go, and they will be pissed if you cut them out. They trained hard for the opportunity to be placed in the best possible situation to close and kill the enemy. If movies depicted this aspect they may appear darker, however it would be significantly more realistic. Little details Something that has always bothered me is when a movie took the time to build the base, used the right tools and understood the mindset, but then missed the little details. An example would be depicting a Ranger and for whatever reason he has a scene where he is in his dress uniform but the ribbons, patches and tabs don’t tell the same story the movie is trying to tell. How can you have a Ranger without a parachutist badge or a tan beret? Or a Navy SEAL without a trident? If you are going to take the time and energy required to make a compelling character, spend the extra 5 minutes required to make sure that their appearance is sound. The devil really is in the details. by Thomas

Let’s talk about war movies. First I would like to say that I don’t presume to know about producing movies, writing scripts or selling entertainment to the masses. That being said what I can do is look at something and apply a realistic mechanism to it that will allow as much realism to pass through as possible. The war condition is a completely unique and extremely personal experience. In every action movie or book when the action flows properly it makes sense and the experience is enriched. There is a fine line between entertaining an audience and depicting realistic war-like conditions. There are some highly popular blockbusters that are well received by civilian audiences and extremely lucrative, however they lack the heart, soul and grit of the experience of war. For example I have never seen a soldier single-handedly defeat 20 enemy combatants with his Leatherman tool. On the other end of the spectrum are the movies that capture the brutality of war and amplify it solely for shock value. We have all seen the movie where the protagonist haunted by his experiences turns into something horribly dark and dangerous. As a combat Veteran I appreciate it when a film captures the action properly (i.e. claymores do not erupt into giant fire balls), the characters involved in the story have depth and meaning, and finally the shared experience of a harrowing event regardless of its outcome. If the characters mean nothing to you, then you don’t understand why his/her comrades are distraught at the loss. The best example of this is Band of Brothers. Band of Brothers bridged the gap between reckless entertainment and overzealous grit. It opened the shutter of the war condition that not only allowed us to experience WW II in a way it had never been seen; it also allowed us to see the little things that worked towards the totality of the experience. The pranks, the trials, the successes and the failures seem small but without them only part of the story is told. So how is this realism obtained? Knowing from first hand experience I can tell you that camaraderie isn’t something that is issued with your uniform and weapon. It is something that can only be achieved through a shared experience. It doesn’t matter if the experience is positive or negative as long as it is shared. Basic training is a systematic break down of a soldier’s built in inhibitions towards different things. You relearn how to eat, fight, work in a team, kill and most importantly take orders without hesitation. If you want to depict a combat situation it is necessary for your actors to experience, albeit watered down, a basic training type regime that prepares them for their roles. I look forward to the future of war movies as long as we can capture events properly and respectfully. That’s not to say I wouldn’t mind seeing a new Rambo movie also! |

Archives

September 2015

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed