by Dustin

A couple of weeks ago Dave and I went down to the Great American Pitchfest in Burbank. I was excited because we had tickets to listen to Luke Ryan, Executive Vice President of Disruption Entertainment, speak about world building. It was an early morning class and at first I thought I had spiked my coffee with something because for several hours he spoke about everything I had been believing for years. It was a tremendously validating moment. "Great", says Dave, "Now write about it."

World building

There are two reasons for building a world bible, one is artistic, the other financial. Artistically, a well-built world will let you tell your story easily and answer questions for you as they arise. This becomes more important as you delve into secondary characters, sequels, and "other" stories in general. From a financial standpoint this "world bible" will also help you change and adapt as the demographics of your audience become more apparent to the marketing firms who are looking at your product and trying to grow your intellectual property. I thought I'd write this article and show you, as an exercise, how easy it is to create a new and vibrant world that can be monetized in several ways.

Let’s pretend we have a story we want to tell about a boy who leaves home and finds adventure only to become the world’s greatest investigator. It's a fairly normal hero arc with an extra bit of growing up thrown in for good measure. Let’s do it in a steampunk universe, that's popular now. The first thing to do is build our world. We start this by defining a couple of large order things:

Excellent! Now we have a story happening in a world that we can draw references from. Our hero can have dreams that lead him down the right path, create new devices, or warn him of impending danger. Does he believe in Nightmare? Is he being controlled by his dreams? He must learn to operate within the strict social confines of Dreamport and will probably make friends and enemies with assorted Emperor Officials throughout his adventures. Will the rebellion play a part in the mystery of our story or is it just backdrop? Now it's time to get to the big part,

World Timelines.

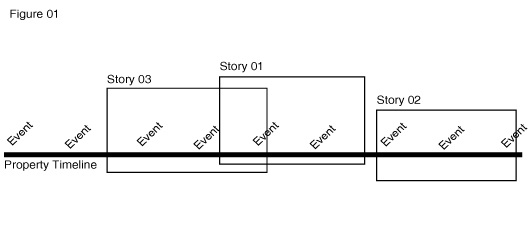

In the real world, historians use meaning to shape the cultural understanding of world events. As the writer, we can use this to our advantage by working in reverse. What is a thematic meaning we want to include? What world events happened to create this meaning and how did historians fold it into the context of our story structure? As you start thinking about this, draw a line on a piece of paper. The beginning of the line is the beginning of our world, and the end is, well, the end. Along this timeline, world events take place. For instance, the discovery of fire, literacy, the fall of Rome, World Wars, Famines, Etc... Whatever large world events are appropriate for the subtextual meanings in your world. See Fig 01.

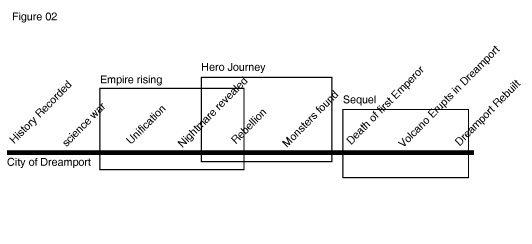

Now box out where your story fits within the timeline. Our story about the boy who becomes Dreamport's lead investigator falls after the rise of the first emperor, shortly after the god "Nightmare" is revealed, takes us through the Rebellion and sees the discovery of monsters. How these large set pieces interact with our storyline is not yet decided (or maybe it has!) but knowing they are there provides the opportunity for a lively backdrop on which to set our stage. Why in the crap would you do this? Seems like a lot of work for just one story doesn't it? It is.

The truth of the matter is that as we aren’t building this world for just one story. We are opening up a new universe in which other people, who we've never met before, can participate in. As we lay down the rules for the universe, other opportunities begin to reveal themselves in the details. This is the crucible in which "Good for the Art" and "Good for Business" find themselves. As our product (the story) comes to market (as a book, or movie, or game etc...) there will be changes both in the response to our product, and to the market as a whole. Having the world bible on hand is essential for weathering and adapting to changes in the market. For instance:

As our first project comes to market, we will be guessing at who our target market will be. Let’s say our story is aimed at teenage males 11-17. During the marketing campaign leading to the release of our young adult novel we find that we have more traction with 26 year old women than our intended audience. Our next project will be aimed at those ladies. But how? By looking at marketing data we find that ladies in the 24-32 year old bracket are playing a lot of games on Facebook (or watching cooking shows, or whatever they may be obsessing with at the time) and we will create one of those. How? By looking at our timeline and finding the best place to let the media cross over. For Dreamport, focusing on the rise of the emperor, setting our story before our young adult novel we will see a slight crossover on the timeline. This might be a good transition to the first project, interlinking characters, or only sharing background with our first novel in order to build the brand. See Fig. 2.

Six months later our numbers on the first young adult book sales are doing terrific. (positive thinking ya'll) So good that a movie company comes along and wants a movie in our world. The smart thing is to have already outlined the second part of our hero's journey. Now we can incorporate both our slightly older teenage market, and our late twenties market, into a popular R rated film. In Dreamport terms, our hero from the book falls in love with the Emperor's concubine, or daughter or something from the second story, and uses their love to destroy the rest of the monster cult. Good job us.

The point of making a world bible on the creative front is to maximize our understanding of the world in which our characters will operate. From a financial standpoint the world bible allows us to operate quickly and efficiently to market changes, and provides a jumping off point for expansion projects when they come up.

For more information about Luke Ryan and his world building lessons, you can follow his world building Twitter feed as well as his world building website.

If you have more questions or thoughts about this article, you can email Dustin at [email protected]

A couple of weeks ago Dave and I went down to the Great American Pitchfest in Burbank. I was excited because we had tickets to listen to Luke Ryan, Executive Vice President of Disruption Entertainment, speak about world building. It was an early morning class and at first I thought I had spiked my coffee with something because for several hours he spoke about everything I had been believing for years. It was a tremendously validating moment. "Great", says Dave, "Now write about it."

World building

There are two reasons for building a world bible, one is artistic, the other financial. Artistically, a well-built world will let you tell your story easily and answer questions for you as they arise. This becomes more important as you delve into secondary characters, sequels, and "other" stories in general. From a financial standpoint this "world bible" will also help you change and adapt as the demographics of your audience become more apparent to the marketing firms who are looking at your product and trying to grow your intellectual property. I thought I'd write this article and show you, as an exercise, how easy it is to create a new and vibrant world that can be monetized in several ways.

Let’s pretend we have a story we want to tell about a boy who leaves home and finds adventure only to become the world’s greatest investigator. It's a fairly normal hero arc with an extra bit of growing up thrown in for good measure. Let’s do it in a steampunk universe, that's popular now. The first thing to do is build our world. We start this by defining a couple of large order things:

- Social Hierarchy - Humans fold themselves into groups and most groups have some kind of social hierarchy. Much steampunk is set in a Victorian Era, and I think we'll twist ours to be more of a feudal japan state, with large houses reporting back to an emperor in the main city of... Dreamport. Where the emperor keeps their families hostage and maintains his grip on the kingdom.

- How Money Works - Each world should have its own money exchange system, from the goblins of Gringotts to the Federal Reserve Notes in Die Hard, Money is a big deal. In many fantasy works, a convoluted change system much the same as the middle ages is used, with copper, silver and gold being currencies. In the world of Dreamport, money will be handled by large banks and identification punch cards are given out to the servant class who purchase things and move goods. The higher castes of people rarely have access to a card and are rarely in a position to use them.

- Political Landscape - Just because the universe is ruled by a representative republic with senators convening on a planet somewhere, doesn't mean that there isn't someone in the background working on his own empire. The political landscape will determine how towns are structured, how police work, and how "normal" families are structured. Dreamport is headed by the Emperor, but run by his officials. They have enormous power, and each is trying to outwit his contemporaries to gain the Emperor’s favor. The Emperor himself cares only about expanding his empire and keeping the peace in Dreamport. The outlying cities and towns are not the Emperor’s care, making the officials kings of their cities and counties. At least one of these counties is in open rebellion to the empire, with the Emperor's official from that county held captive on house arrest in Dreamport.

- Theological Landscape - But what of the gods? Many fantasy novels invoke the gods as powers that cannot be understood or have their own agendas. Sci-Fi often has a society that has given up on the idea of gods and embraced Science as their motivating force. Whichever way you look at it, people usually need a way to explain away the unexplainable, and you need all the motivational tropes you can get in order to create tension for your story. The main religion of Dreamport will be the worship of Nightmare, the god of dreams and transportation. All good ideas and inspiration are thought to come from Nightmare. Bad dreams are warnings. There should also be a pantheon of gods thought to be worshiped for different reasons; from taking a safe journey to having a late nightcap. All are minions, or versions, of Nightmare.

- Technological Capabilities - Is it swords? Trains? Teleportation? What are the normal things that people in your world have access to? In many medieval fantasies the normal person does not have access to arms and armor, horses or etc... In some cyberpunk everyone has a gun, but not a television. Our story in Dreamport will start with a boy who has limited access to many things. Through his journey he'll gain access to different technologies, weapons, and transportation. Police have access to a certain level of gear, batons and stun gun type things. The military is sword based with large smashing devices and steam powered shooting devices.

Excellent! Now we have a story happening in a world that we can draw references from. Our hero can have dreams that lead him down the right path, create new devices, or warn him of impending danger. Does he believe in Nightmare? Is he being controlled by his dreams? He must learn to operate within the strict social confines of Dreamport and will probably make friends and enemies with assorted Emperor Officials throughout his adventures. Will the rebellion play a part in the mystery of our story or is it just backdrop? Now it's time to get to the big part,

World Timelines.

In the real world, historians use meaning to shape the cultural understanding of world events. As the writer, we can use this to our advantage by working in reverse. What is a thematic meaning we want to include? What world events happened to create this meaning and how did historians fold it into the context of our story structure? As you start thinking about this, draw a line on a piece of paper. The beginning of the line is the beginning of our world, and the end is, well, the end. Along this timeline, world events take place. For instance, the discovery of fire, literacy, the fall of Rome, World Wars, Famines, Etc... Whatever large world events are appropriate for the subtextual meanings in your world. See Fig 01.

Now box out where your story fits within the timeline. Our story about the boy who becomes Dreamport's lead investigator falls after the rise of the first emperor, shortly after the god "Nightmare" is revealed, takes us through the Rebellion and sees the discovery of monsters. How these large set pieces interact with our storyline is not yet decided (or maybe it has!) but knowing they are there provides the opportunity for a lively backdrop on which to set our stage. Why in the crap would you do this? Seems like a lot of work for just one story doesn't it? It is.

The truth of the matter is that as we aren’t building this world for just one story. We are opening up a new universe in which other people, who we've never met before, can participate in. As we lay down the rules for the universe, other opportunities begin to reveal themselves in the details. This is the crucible in which "Good for the Art" and "Good for Business" find themselves. As our product (the story) comes to market (as a book, or movie, or game etc...) there will be changes both in the response to our product, and to the market as a whole. Having the world bible on hand is essential for weathering and adapting to changes in the market. For instance:

As our first project comes to market, we will be guessing at who our target market will be. Let’s say our story is aimed at teenage males 11-17. During the marketing campaign leading to the release of our young adult novel we find that we have more traction with 26 year old women than our intended audience. Our next project will be aimed at those ladies. But how? By looking at marketing data we find that ladies in the 24-32 year old bracket are playing a lot of games on Facebook (or watching cooking shows, or whatever they may be obsessing with at the time) and we will create one of those. How? By looking at our timeline and finding the best place to let the media cross over. For Dreamport, focusing on the rise of the emperor, setting our story before our young adult novel we will see a slight crossover on the timeline. This might be a good transition to the first project, interlinking characters, or only sharing background with our first novel in order to build the brand. See Fig. 2.

Six months later our numbers on the first young adult book sales are doing terrific. (positive thinking ya'll) So good that a movie company comes along and wants a movie in our world. The smart thing is to have already outlined the second part of our hero's journey. Now we can incorporate both our slightly older teenage market, and our late twenties market, into a popular R rated film. In Dreamport terms, our hero from the book falls in love with the Emperor's concubine, or daughter or something from the second story, and uses their love to destroy the rest of the monster cult. Good job us.

The point of making a world bible on the creative front is to maximize our understanding of the world in which our characters will operate. From a financial standpoint the world bible allows us to operate quickly and efficiently to market changes, and provides a jumping off point for expansion projects when they come up.

For more information about Luke Ryan and his world building lessons, you can follow his world building Twitter feed as well as his world building website.

If you have more questions or thoughts about this article, you can email Dustin at [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed